Isprava’s Gleneagle Estate’s owner, authors an article on one of the biggest issues of the moment— Sustainability

An in-depth, comprehensive report on sustainable living, responsibility

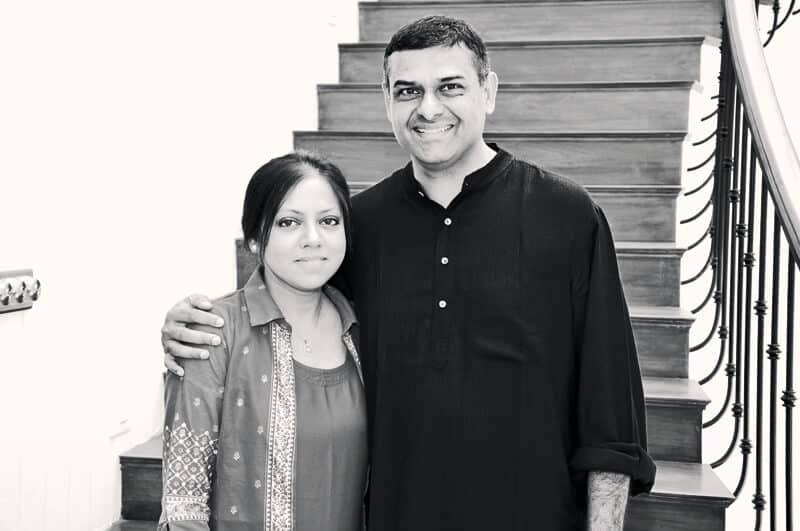

and development written by Mukund Rajan, homeowner of Isprava’s

Gleneagle Estate

Iam the proud owner of Gleneagle Estate, a lovely property built for my wife and me by Isprava in the Nilgiri Hills. Our property is nestled amidst hills, forests and tea plantations in an environment that is still quite unspoilt. The air you breathe is possibly the cleanest and most invigorating you could hope for anywhere in India, and daytime temperatures throughout the year typically stay within a high of the mid-twenty degrees centigrade.

At a time when India has the dubious record of hosting ten of the twenty most polluted cities in the world, having the option of getting away from the pollution and the summer heat to the idyllic surroundings of Gleneagle Estate is truly a blessing. And as the serving Chairman of the Environment Committee of the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), I count my blessings every day when I see the sad situation that many parts of our country face to achieve sustainable development.

For several decades after India gained independence from the British colonial rule, the developmental agenda took precedence, natural for an extremely poor country. At the 1972 Stockholm United Nations Conference on Human Environment, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called this out in a famous speech where she said “poverty is the greatest polluter”. While this period saw some significant conservation initiatives such as Project Tiger, to restore the population of tigers in India by addressing human-animal conflict in tiger habitats across India, the focus was nevertheless clearly on developmental priorities.

In more recent times, though, with growing awareness of water and air pollution, and the impetus provided by tragedies like the Bhopal gas leak in 1984, a number of actions have been undertaken including the enactment of legislations like the Air and Water Acts and the Environment Protection Act, and the creation of the Ministry of Environment and Forests at the centre in Delhi to give better definition to the country’s approach to sustainable development. The number of laws and rules and regulations in place at both the centre and the states in India is, however, no guarantee for protection of the environment, as we see creeping crises emerge in a range of areas, from water stress in rural areas and even major cities like Chennai, to air pollution in the national capital. A key requirement is more effective monitoring and policing of environmental compliance, where stakeholders from the media and the non-profit sector have an important role to play in assisting the government.

Aggravating the situation is the emergence of global environmental issues which present unique challenges. These issues, like global warming, ozone depletion and the loss of biodiversity, call for international cooperation; no one nation can solve these problems on its own, and the collaboration of all countries is required for their resolution. On an issue like global warming, for example, it is of little use if the major economies of the developed world, the United States and the European Union, implement significant actions to curb their greenhouse gas emissions, unless two of the top three greenhouse gas emitters in the world, namely China and India, also join hands to reduce their emissions. A consensus is required between all countries, to ensure the available global carbon budget is distributed rationally.

We are beginning to experience the extremely grave threats posed by global environmental issues like global warming. The increased frequency of natural calamities like the Uttarakhand floods of 2013 which killed many thousands, or the unprecedented floods that struck Chennai in 2015 or Kerala last year, are a harbinger of things to come. As the third largest greenhouse gas emitter in the world, India will need to play a big role in resolving the issue of climate change, and this will require the collaboration of the government with all stakeholders to develop a national strategy to combat climate change. Already, under the framework of the Paris Climate Pact, the Indian government has undertaken to reduce the carbon intensity of its GDP by 33-35% over 2005 levels by 2030, and to produce 40% of its energy through renewables by 2030. More will progressively need to be done, as the world and India race to deal with the forecast of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change late last year that global warming is happening now at amuch faster pace than was projected earlier.

At a critical time like this, when there are high mutual interdependencies between the major economies of the world, the role of the United Nations also becomes very important. In 2015, its work led to the adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals or SDGs. The UN SDGs today offer the most comprehensive framework for the pursuit of sustainability, with 17 SDGs traversing issues ranging from poverty alleviation to enhancing gender equality, in turn translating into 169 targets the international community would like to see achieved by 2030. The biggest motivation for the adoption of the UN SDGs is the growing confidence that greater awareness and advances in science and technology now offer the ability to find solutions for all the SDG challenges.

The combination of domestic laws and rules and regulations, and international frameworks and treaties, place many responsibilities on the shoulders of the largest contributors to the sustainability challenges we face, namely the corporate sector. Indian corporates are being tasked to report and make better disclosures on sustainability. A number of Indian companies already use the Global Reporting Initiative framework. The market regulator SEBI has recently encouraged the adoption of Integrated Reporting by India’s largest listed companies. The government has also recently issued new National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct, and these are expected to feed into the Business Responsibility Reports that the top 500 listed companies in India are required to file (likely to soon be extended to the top 1000 companies).

Indian corporates are also beginning to embrace the concept of the “circular economy”, one where resources are circulated within the system releasing minimal waste into the biosphere. A number of new enterprises are being created to retrieve what would earlier be considered “waste” and convert both wet and dry waste into usable products. New business models are springing up, in areas like the sharing economy (think Uber or Ola) or productivity enhancement (as offered by Philips when it prices luminosity as a service rather than as a set of light bulb products). Large companies, including some auto makers, are making big investments in design thinking, after undertaking full life-cycle assessments of their products. They are also beginning to value and report on the various forms of capital they manage, including natural capital and social capital, factoring in the whole life-cycle value of the costs and risks embedded in the products and services they produce.

“THE ENTIRE SUSTAINABILITY AGENDA IS NOW BECOMING A PART

OF MAINSTREAM CORPORATE STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT AND THE

RESPONSIBILITY OF THE CEO, WITH BOARD OVERSIGHT

The new challenges of sustainability are spurring corporate innovation and the quest for new business opportunities. Corporates see that by responding to the sustainability trends with agility—they can not only remain competitive, mitigate risks, and future proof their businesses, but also be well positioned to seize the business

opportunities that get unlocked as a result. Significant market opportunities are being created in India in sectors ranging from solar power equipment to drip irrigation modules to electric vehicles, all a result of the new focus

on sustainability.

Corporates are also being responsive to the increase in the number of consumers, especially millennials, who are becoming more inclined to buy products or services that align with their own lifestyles and value systems. For such consumers, it is no longer about what you buy, but what you buy into. If businesses are willing to clarify the higher purpose they serve, customers are also willing to reward them with both mind-share and share of wallet. Corporates that offer purpose-driven brands, like “Tata”, whose Mission is to ‘Improve the Quality of Life of the Communities We Serve”, or “The Body Shop”, which commits to ‘Enrich, not Exploit’, consequently tend to get good traction in the market.

As with corporations elsewhere, Indian corporates are also facing scrutiny on the sustainability actions of their supply chain participants. Today, for instance, if an Indian

tea company, say Tata Global Beverages, wishes to sell tea in markets across the world, it has to be very concerned about the treatment of labour and the sustainability practices followed in plantations across India, Sri Lanka, Kenya and various other parts of the world from where it sources the tea it sells.

The net impact of all of these trends—the quest for a circular economy, new protocols to value social and natural and other forms of capital, the thrust on innovation, and the growing consumer affinity for purpose-driven brands —is that in India, the most forward-looking corporates are beginning to place sustainability at the heart of their business strategies, as Unilever, a global role model has done with its Sustainable Living Plan. Indeed, the entire sustainability agenda is now becoming a part of mainstream corporate strategy development and the responsibility of the CEO, with Board oversight.

It is also noteworthy that India has gone one step further than most other countries in outlining the responsibilities of the corporate sector. It has taken the lead in legislating expectations from corporates in the area of Corporate Social Responsibility or CSR. In a first-of-its kind legislation anywhere in the world in 2013, corporates in India that meet a size and scale test are required to spend 2% of their net profits on CSR. This spending is required to be monitored by a committee of the Board of Directors, which includes an Independent Director. This scrutiny is elevating the discourse on CSR at the level of the Board—where earlier CSR spending by Indian companies used to be something undertaken “beyond business”, if and when a corporate had the money and inclination, it is now a firm mandate, and a matter of considerable debate and discussion amongst Board Directors, with a focus on the efficiency of spending and the outcomes delivered. In addition, in the more forward- looking corporates, we are seeing the mandate of such Board committees expand, to include the larger subject of sustainability.

Corporate engagement with the sustainability agenda is now the subject of great interest for investors around the world. This is the reason that an increasing number of investors are focussed on the Environment, Social and Governance, or ESG, performance of their portfolio companies. This is the reason that Larry Fink, the head of one of the world’s largest institutional investors, BlackRock, advises CEOs in his annual letter that “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society. Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate.”

Mukund Rajan, Chairman of ECube Investment Advisors, an ESG focused platform, was earlier Chief Ethics Officer of the Tata Group and Chairman of the Tata Global Sustainability Council. A published author, this IIT Delhi and Oxford alumnus has a fresh new focus on all things to do with environmental sustainability.

ESG is now the fastest growing investment approach globally, with over $70 Trillion of assets under management committed to the UN Principles for Responsible Investing (PRI). This number will increase as new regulations emerge in markets like the European Union, where it will soon become a requirement for all asset managers to disclose the ESG performance of their investment portfolios. Studies show a correlation between material ESG actions and firm outcomes, and these outcomes in terms of better performance and reduced risk improve when there is active engagement. That is precisely the thesis that underlies the ESG Fund I have launched recently. We intend to incentivise Indian companies that are already on or prepared to get onto the ESG performance improvement journey, and will demonstrate through our investee companies that a focus on ESG can yield lower cost of operations, risk reduction, lower cost of borrowing, and greater prospects for valuation rerating.

So, as members of key stakeholder groups that can impact the sustainability agenda—be it as part of the government, or in the corporate sector, or in the non-profit sector, or as an investor or lender—we each have a responsibility to fulfil.

But equally, let us not forget that each of us can also individually exercise judgment and support what is right, whether it is in the selections we make as a customer, or as a volunteer willing to dedicate time and skills for improving the focus on sustainability. Ask yourself whether you are doing the best you can to reduce your climate footprint. Do you reduce your individual carbon footprint by limiting your consumption of petrol, and do you use mass mobility solutions when available? Do you minimize your use of power, and use air-conditioning moderately? Do you limit your water usage, and have you implemented solutions like rain-water harvesting in your home? Do you reduce plastic usage, and are you trying to eliminate the use of single-use plastic products wherever possible such as plastic straws, stirrers and cups? Do you segregate garbage, and re-use and repair items instead of discarding them?

In conclusion, let us remember the prophetic words of the Father of our Nation, Mahatma Gandhi—the world has enough for every person’s need, but not for every person’s greed!

By Mukund Govind Rajan ([email protected])